Introduction

- The ongoing farmers’ protest is against the three farm acts passed by the Indian Parliament in 2020.

- The acts have been described as "anti-farmer laws" by some farmer unions. Soon after the acts were introduced, unions began holding local protests, mostly in the states of Punjab and Haryana.

- They want a complete rollback of the farm laws.

- Farmers from aforementioned states also began a movement named 'Dilli Chalo' (Let's go to Delhi), in which tens of thousands of farmers marched towards the national capital.

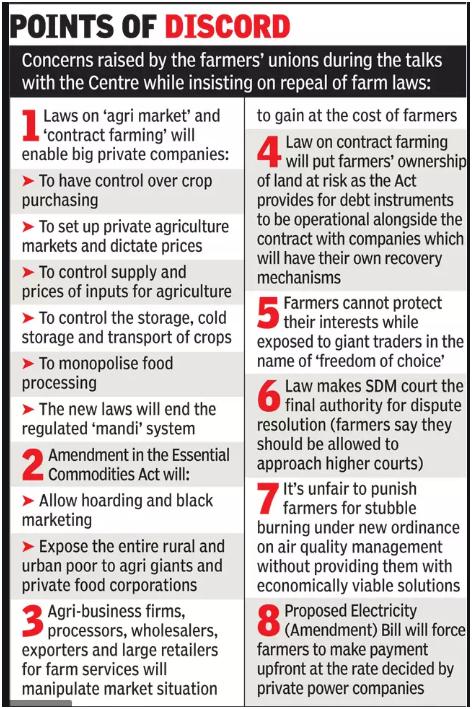

What are the reasons behind the Protests?

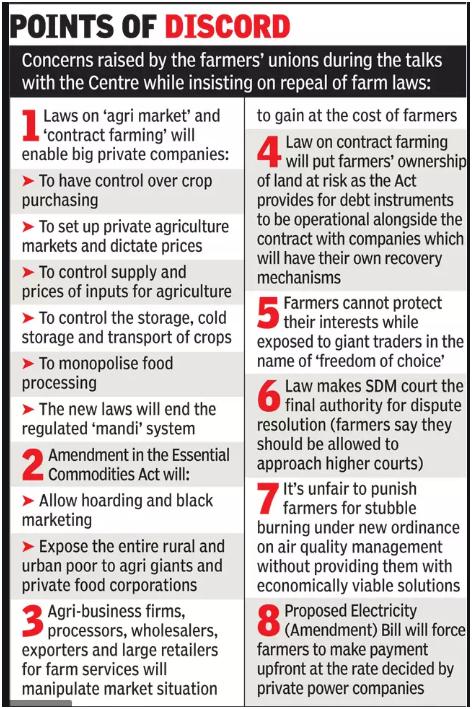

- Three laws: Farmers do not accept the three new legislations — The Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation); The Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement of Price Assurance; and Farm Services and The Essential Commodities (Amendment).

1. The Farmers' Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act, 2020

- It allows trading in an "outside trade area" like farm gates, factory premises, warehouses, silos, and cold storages. Earlier, agricultural trade could be conducted only in the APMC yards/ Mandis.

- It will also facilitate lucrative prices for the farmers through competitive alternative trading channels to promote barrier-free inter-state and intra-state trade of agriculture goods.

- The Act also permits the electronic trading of farmers' produce in the specified trade area. It will facilitate direct and online buying and selling of such produce through electronic devices and internet.

- The act prohibits state governments from levying any market fee or cess on farmers, traders and electronic trading platforms for trading farmers’ produce in an 'outside trade area'.

2. The Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Act, 2020

- The Government asserts that the Act helps protect farmers engaging with Agri-business firms, processors, wholesalers, exporters or large retailers for farm services and sale of future farming produce by a mutually agreed lucrative price framework in a fair and transparent manner through a contract.

- The Act provided for a three-level dispute settlement mechanism by the conciliation board, Sub-Divisional Magistrate and Appellate Authority.

- The agreement had to provide for a conciliation board as well as a conciliation process for settlement of disputes.

3. The Essential Commodities (Amendment) Act, 2020

- Regulation of food items: The Essential Commodities Act, 1955 empowers the central government to designate certain commodities (such as food items, fertilizers, and petroleum products) as essential commodities.

- The central government may regulate or prohibit the production, supply, distribution, trade, and commerce of such essential commodities.

- The Act provides that the central government may regulate the supply of certain food items including cereals, pulses, potatoes, onions, edible oilseeds, and oils, only under extraordinary circumstances. These include:

- War

- Famine

- extraordinary price rise

- natural calamity of grave nature

- Stock limit: The Act requires that imposition of any stock limit on agricultural produce must be based on price rise.

- A stock limit may be imposed only if there is:

- a 100% increase in retail price of horticultural produce

- a 50% increase in the retail price of non-perishable agricultural food items.

- The increase will be calculated over the price prevailing immediately preceding twelve months, or the average retail price of the last five years, whichever is lower.

|

- Fear of end of mandi system: They believe the laws will open agricultural sale and marketing outside the notified Agricultural Produce Market Committee (APMC) mandis for farmers, remove the barriers to inter-state trade, and provide a framework for electronic trading of agricultural produce.

- Since the state governments will not be able to collect market fee, cess or levy for trade outside the APMC markets, farmers believe the laws will gradually end the mandi system and leave farmers at the mercy of corporates.

- Fear of loosing the assured procurement: Farmers believe that dismantling the mandi system will bring an end to the assured procurement of their crops at MSP. Farmers are demanding the government guarantee MSP in writing, or else the free hand given to private corporate houses will lead to their exploitation.

- Loosing the arhtiyas and farmers relationship: The arhtiyas (commission agents) and farmers enjoy a friendship and bonding that goes back decades. On an average, at least 50-100 farmers are attached with each arhtiya, who takes care of farmers’ financial loans and ensures timely procurement and adequate prices for their crop. Farmers believe the new laws will end their relationship with these agents and corporates will not be as sympathetic towards them in times of need.

What does the government say?

- Historic reforms: The Government has backed the bills as historic reforms, which will open up agricultural markets, giving more options to farmers other than notified market yards to sell their produce.

- Freedom to sell anywhere: The three farm laws have been projected by the government as major reforms in the agriculture sector that will remove middlemen and allow farmers to sell anywhere in the country.

- Until 2020, the first sale of agriculture produce could occur only at the mandis of the Agricultural Produce Marketing Committee (APMC).

- However, after the Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act, 2020 came into force it allows farmers to sell outside APMC mandis in India.

- Beneficial for traders and consumers as well: The Centre said that it will be beneficial to not only farmers but also traders and consumers.

- Engagement in direct marketing: The government has also said that farmers will be able to engage in direct marketing of their crops.

What are the provisions under the new laws?

- Farmers will be to enter into a contract with processors, wholesalers, aggregators, large retailers and exporters directly so as to realise the full price of the produce

- Farmers be rest-assured of the price of their produce even before sowing of crops

- Farmers will not be charged any cess or transport cost at the time of sale

- Farmers will get access to modern technology, better seed and other inputs that enable better growth of the produce

|

Rational behind new farm legislation

- Is MSP mechanism beneficial to all farmers?

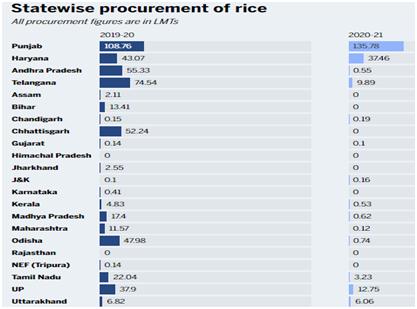

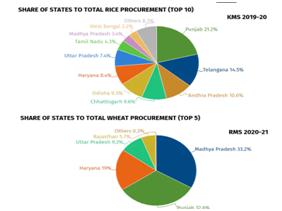

- The MSP mechanism for wheat is robust only in Punjab, Haryana and Madhya Pradesh.

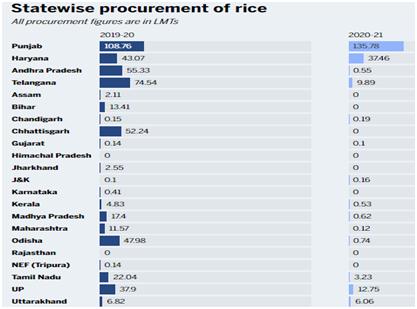

- For rice, only farmers from states such as Andhra Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Punjab and Haryana benefit.

- Farmers in other states hardly benefit from support prices because the government’s procurement infrastructure is missing in these states.

- The 70th round of National Sample Survey for 2012–13 revealed that only 32.2% of paddy farmers and 39.2% of wheat growers in the country were aware of MSPs.

- The survey also showed that only 13.5% of paddy farmers actually benefited from MSP, while only 16.2% growers sold their produce to government procurement agencies at MSP prices.

- For commercial crops, such as cotton and jute, the state intervenes through the Cotton Corporation of India and Jute Corporation of India only when market prices fall steeply.

Minimum Support Price & Issues

- MSP is the minimum price paid by the government when it procures any crop from the farmers.

- It is announced by the state-run Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP) for more than 22 commodities on an annual basis, after calculating the cost of cultivation.

- Food Corporation of India (FCI) which is the main state-run grain procurement agency largely buys only paddy and wheat at these prices.

- The FCI then sells these foodgrains at highly subsidised prices to the poor and is thereafter compensated by the government for its losses.

- However, the FCI procurement is not uniform across India. In Bihar, for example, procurement by FCI has remained at less than 2 per cent of the state's total production.

- Therefore, most farmers are forced to sell at a discount of about 25 per cent to 35 per cent of MSP. But millions of tonnes of paddy and wheat are procured from the states of Haryana and Punjab.

|

- Is procurement of all commodities feasible?

- It is not feasible for public agencies to procure the marketed surplus of each and every commodity everywhere in the country to prevent prices falling below a floor level; nor would this be desirable.

- New mechanisms were required to protect producers against the prices falling below the threshold level.

- Over-exploitation of groundwater resource: Availability of cheap power and water and assured procurement at a price that is higher than the market rate has got the farmers in the northern states hooked on to paddy and rice which led to unplanned and over-exploitation of groundwater resource.

- Import: Farmers make little effort to diversify into other crops, such as oil seeds and pulses that India still needs to import.

Why farmer’s protests have been loudest in Punjab and Haryana and not in other states?

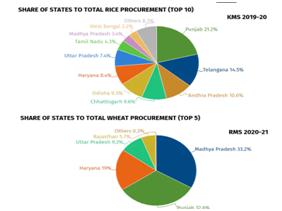

Punjab and Haryana hold high share in MSP procurement

- The FCI procurement data makes it obvious why farmers from Punjab and Haryana are more apprehensive about any changes in MSP laws.

Making APMCs and procurement systems consequential:

- The other concern among farmers is making APMCs and procurement systems inconsequential.

- Neither do the laws say anything about it [abolishing the MSP system and dismantling APMC mandis], nor is the MSP/APMC system going to disappear with these laws.

- What would certainly come under pressure is the high commission of arhtiyas, mandi fees and cess that states collect, which account for as much as 8.5 percent over the MSP in Punjab, amounting to roughly Rs 4,500 to Rs 5,000 crore each year.

Agricultural Produce Market Committee (APMC):

- Agricultural Produce Market Committee (APMC) is a marketing board established by state governments in India to ensure farmers are safeguarded from exploitation by large retailers, as well as ensuring the farm to retail price spread does not reach excessively high levels.

- APMCs are regulated by states through their adoption of a Agriculture Produce Marketing Regulation (APMR) Act.

- Until 2020, the first sale of agriculture produce could occur only at the market yards (mandis) of APMC.

- However, the Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act, which came into effect in 2020, allowed farmers to sell outside APMC mandis in India.

Which states have APMC?

- Kerala, Manipur, Mizoram and Sikkim along with the UTs like Andaman & Nicobar Islands, Lakshadweep, Daman & Diu, and Dadra and Nagar Haveli never had an APMC, law whereas Bihar repealed it in 2006.

- In 2013 vegetables and fruits were shifted out of APMCs.

- Since 2002, close to 69 to 73 percent of the production left with the farmers was sold outside APMCs below the minimum support price (MSP).

- As per a NSSO report of 2016, only 36 percent of the trading could be identified to take place in the regulated market.

|

High Commissions

- The Arhatiya community, as the commission agents are called in Punjab and Haryana, is very strong in these two states.

- In these two states in which agricultural land is predominantly held by the large farmers, the agriculturists are far better off than the other parts of the country.

- Apart from these states, agriculture is no longer considered an economically viable way of livelihood.

- So the two states turning into the womb of agitation against the new farm laws need a little introspection.

Where farmers actually sell their produce?

- The NSS70th round survey shows that the majority of farm output at the national level is sold to local private traders, followed by mandis.

- The lower share of sale to cooperative and government agencies shows the lesser utilisation of procurement agencies which provide Minimum Support Price (MSP) to selected crops.

- The NSS survey findings also indicate that the majority of agriculture production in the country is for own consumption.

- Less than 10% of all crops are today sold at the MSP to government procurement agencies, so if the majority of farmers are selling to private traders even today, it is difficult to argue a catastrophe is around the corner if the MSP system goes; that is why the agitation is really limited to states like Punjab.

Does awareness of MSP have a role?

- A report by the NITI Aayog released in 2016, on the evaluation of MSPs-based on a survey of a few states noted that all households surveyed in Punjab sold their produce at MSP and none in the open market.

- On the contrary, the proportion of sale at MSP was lower in other states.

- All the farmers in Punjab were aware about MSP while the proportion of farmer awareness was lower among other states.

- Of 11 states, all farmers surveyed from four states--Andhra Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand were aware of MSP.

- However, it also needs to be highlighted that when it comes to major crops like wheat and paddy, large farmers corner the benefits. For instance,

- Large farmers in Punjab consumed only 24 percent of their wheat produce and sold 47 percent at MSP.

- Small farmers consumed 53 percent of their produce and sold 27 percent at MSP.

- Survey findings showed that farmers in three of the six sample states considered for wheat (Bihar, Gujarat and Uttarakhand), and three of the eight states for paddy (Gujarat, Karnataka and Maharashtra) did not sell at the MSP at all.

Can farmers go to court?

- To resolve disputes, farmers can seek out a so-called conciliation board, district-level administrative officers or an appellate authority.

- However, these cases will not go to a regular court.

Internationalization of the issue

- Vested interests: Indian farmers have grievances, which they are addressing through the right to protest. But it has been witnessed that the efforts to internationalize India's farmer protest are being led by vested interests.

- Concerns of India: India is concerned over the recent attempts by the extremists and Khalistani elements to influence the decision-making process and polity in Canada and UK on the farmer protest issue.

- UK: A significant number of 36 UK MPs who had expressed their "concern" against farmer protests.

- Canada: Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau showed his support for the farmers protests in India. The seperatist outfit was emboldened by the stance taken by Canadian Prime Minister.

- USA: USA too is not immune from attempts to instigate anti-India sentiments, sources claimed, adding that ISI has been behind several protests in the past against Indian mission in Washington by luring some members of the Sikh community.

- US-headquartered pro-Khalistan outfit Sikhs for Justice (SFJ) has threatened to shut down consulates in various cities across the world in light of the farmers' protests.

Conclusion:

Though, agricultural reforms were long overdue, because the current system is corruption-prone and monopolistic. There is need to protect the interest of farmers that are protesting. At the same time, there is need to remove many restrictions on trade in agricultural commodities so as to stabilise food markets and help agricultural growth. Hence, the government should engage in a meaningful dialogue with total sincerity to find a solution to the situation.