Introduction:

- As India and China compete for influence in South Asia, both are keen to cultivate relations with Bangladesh, which boasts a strategic location, large population, markets and a strong manufacturing sector.

- Beijing has been especially generous in its efforts to charm Bangladesh.

- Seven “friendship bridges” have been built by China over the last several years and, in 2018, China became Bangladesh’s largest source of foreign direct investment, replacing India.

- China is now the country’s largest trading partner and has funded a number of infrastructure projects.

- In addition of the above, Dhaka has begun to discuss a Chinese loan to manage the river.

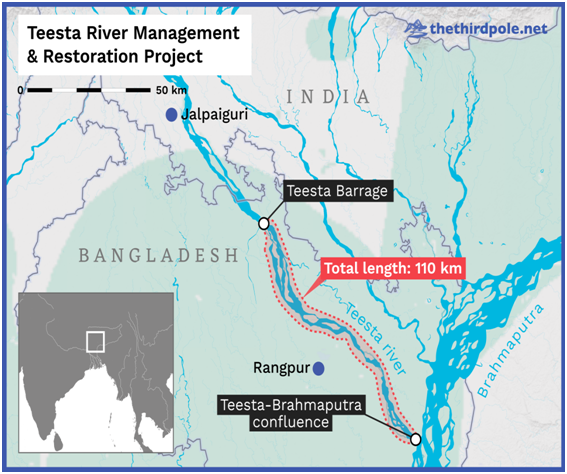

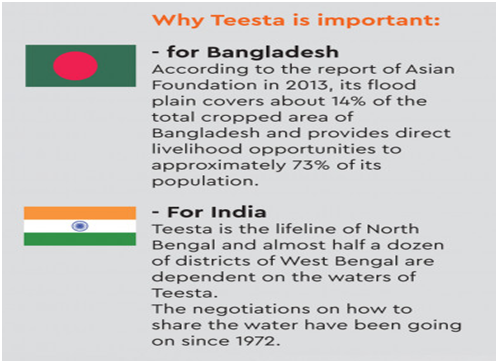

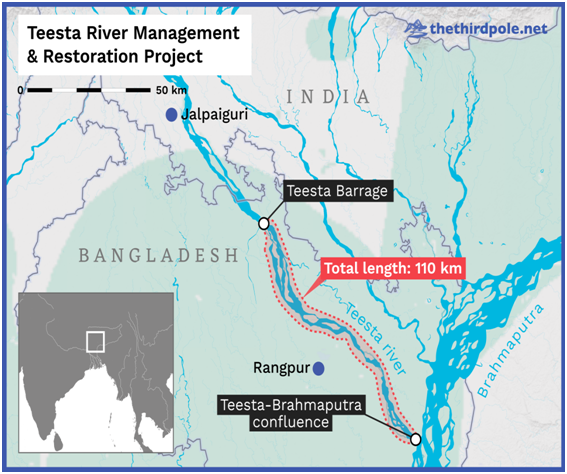

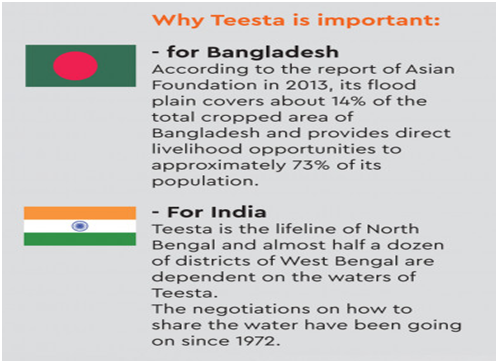

- Bangladesh is discussing an almost $1 billion loan from China for a comprehensive management and restoration project on the Teesta river. The project is aimed at managing the river basin efficiently, controlling floods, and tackling the water crisis in summers.

- India and Bangladesh have been engaged in a long-standing dispute over water-sharing in the Teesta.

- More importantly, Bangladesh’s discussions with China come at a time when India is particularly wary about China following the standoff in Ladakh.

India’s relationship with Bangladesh

- New Delhi has had a robust relationship with Dhaka, carefully cultivated since 2008, especially with the Sheikh Hasina government at the helm.

- India has benefited from its security ties with Bangladesh, whose crackdown against anti-India outfits has helped the Indian government maintain peace in the eastern and Northeast states.

- Bangladesh has benefited from its economic and development partnership.

- Bangladesh is India’s biggest trade partner in South Asia.

- Bilateral trade has grown steadily over the last decade: India’s exports to Bangladesh in 2018-19 stood at $9.21 billion, and imports from Bangladesh at $1.04 billion.

- India also grants 15 to 20 lakh visas every year to Bangladesh nationals for medical treatment, tourism, work, and just entertainment.

- For India, Bangladesh has been a key partner in the neighborhood first policy — and possibly the success story in bilateral ties among its neighbors.

- However, there have been recent irritants in the relationship. These include:

- the proposed countrywide National Register of Citizens (NRC)

- the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA)

|

What are China’s plans on Teesta?

- In September 2016, the Bangladesh Water Development Board entered into a memorandum of understanding (MoU) with Powerchina or the Power Construction Corporation of China to carry out a technical study to better manage the Teesta for the benefit of northern Bangladesh’s greater Rangpur region.

- The China-Bangladesh plan includes:

- extensive dredging of the river and its many tributaries

- the building of dams

- reclamation of land wherever necessary

- stopping the erosion of the embankments during the monsoon months

- help in the maintenance of a certain level of water during the lean season.

- A large reservoir to store water is also part of the plan.

- The overall project will free substantial land from the river’s embankments and allow Bangladesh to build new economic zones.

- Bangladesh requires around $987.27 million for the Teesta River Comprehensive Management and Restoration Project.

- Officially, Bangladesh maintains that it has been in talks with the World Bank, the Japan International Cooperation Agency, and the Government of China.

Will the Chinese project hurt India’s negotiations with Bangladesh on Teesta water-sharing?

- China can put up a tough challenge if it can construct this approximately $1 billion river irrigation and rejuvenation project on one of the toughest Himalayan rivers.

- The impact will also be in the display of China’s engineering abilities. The project will not get Bangladesh the additional water from the Teesta that India alone can provide during the lean season.

- However, it will reduce the annual devastation that the river causes during the monsoon months. This will allow Bangladesh to use the water of the Teesta optimally as a dredged river can be “managed” better during the lean months.

- The Chinese investment is expected to enable Bangladesh to bolster its capacity and use more water from the river by improving water-use efficiency while reducing the losses from floods and riverbank erosion in the short-term (although it has also raised environmental concerns).

- However, the hydrological linkages between India and Bangladesh are a product of geography and a matter of shared history.

- Chinese investment is simply another source of funding for Bangladesh. Contrary to the popular narrative of Bangladesh getting entangled in China’s “debt trap,” evidence suggests that Bangladesh can engage responsibly with China to fuel its next phase of economic growth.

- It will also be the first time that China will construct a mega river management project in Bangladesh.

The Teesta River

- The Teesta River originates at TsoLamo, India, and flows through the states of Sikkim and West Bengal in India and the Rangpur division in Bangladesh before pouring into the Brahmaputra River at Chilmari, Bangladesh.

- The TsoLamo Lake, located 5,280 m above sea level, is the origin of the Teesta River, which is fed by the TeestaKhangse glacier descending from the Pahaunri peak located on the India-China border in North Sikkim.

- The river first flows as a small stream named Lachen Chu up to Chungthang where it joins Lachung Chu and takes the name Teesta.

- Total length- 414 km with an average annual flow of 60 billion cubic meters (BCM) of water.

- Total Area- 12,159 km Within India, 6930 km2 or 86% of the basin lies in Sikkim.

- Teesta is the fourth largest river among the 54 rivers shared by India and Bangladesh

Where the dispute originated?

- Historically, the root of the disputes over the river can be located in the report of the Boundary Commission (BC), which was set up in 1947 under Sir Cyril Radcliffe to demarcate the boundary line between West Bengal (India) and East Bengal (Pakistan, then Bangladesh from 1971).

- In its report submitted to the BC, the All India Muslim League demanded the Darjeeling and Jalpaiguri districts because they are the catchment areas of the Teesta river system.

- It was thought that by having the two districts, the then and future hydro projects over the river Teesta in those regions would serve the interests of the Muslim-majority areas of East Bengal. Members of the Indian National Congress and the Hindu Mahasabha opposed this.

- Both, in their respective reports, established India’s claim over the two districts. In the final declaration, which took into account the demographic composition of the region, administrative considerations, and ‘other factors’ (railways, waterways, and communication systems), the BC gave a major part of the Teesta’s catchment area to India.

- The main reason to transfer major parts of Darjeeling and Jalpaiguri to India was that both were non-Muslim-majority areas.

- Darjeeling had a 2.42% Muslim population while Jalpaiguri had 23.02% Muslims. The League’s claim was based on ‘other factors’.

- During East Bengal’s days as a part of Pakistan, no serious dialogue took place on water issues between India and East Pakistan.

- After the liberation of East Pakistan and the birth of a sovereign Bangladesh in 1971, India and Bangladesh began discussing their transboundary water issues.

The timeline

- Joint Rivers Commission: In 1972, the India-Bangladesh Joint Rivers Commission was established. In its initial years, the most important concerns of water bureaucrats from both countries were the status of the river Ganges, construction of the Farakka barrage, and sharing of water from the rivers Meghna and Brahmaputra. Although the issues related to the distribution of waters from the Teesta were discussed between India and Bangladesh, the river gained prominence only after the two countries signed the Ganga Water Treaty in 1996.

- Sharing of waters: In 1983, an ad hoc arrangement on sharing of waters from the Teesta was made, according to which Bangladesh got 36% and India 39% of the waters, while the remaining 25% remained unallocated.

- Draft on Teesta (2010): After the Ganga Water Treaty, a Joint Committee of Experts was set up to study the other rivers. The committee gave importance to the Teesta. In 2000, Bangladesh presented its draft on the Teesta. The final draft was accepted by India and Bangladesh in 2010.

- New formula: In 2011, during then Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh’s visit to Dhaka, a new formula to share Teesta waters was agreed upon between the political leadership of the two countries. But West Bengal’s chief minister Mamata Banerjee, who was then in a coalition with the Union government, opposed the agreement.

- Even when the Narendra Modi government accepted the new arrangement between India and Bangladesh, Banerjee did not. In 2015, during Modi’s visit to Dhaka to exchange the ratified papers of the Land Boundary Agreement between India and Bangladesh, Banerjee joined him. But she maintained a silence over the issue of sharing Teesta waters.

Major points of contention

- Lean season flow: The point of contention between India and Bangladesh is mainly the lean season flow in the Teesta draining into Bangladesh. The Gazaldoba barrage in West Bengal, about 30 kilometers upstream of Jalpaiguri, has been instrumental in scripting Bangladesh’s misfortune as a downstream riparian state. From 1999 to 2006, the minimum monthly outflow at Kaunia station in Bangladesh for the months between December and April never exceeded 100 cubic meters per second as a bulk of the water was diverted through canals from the barrage.

- Looking towards the future, the influence of potential climate change will increase the probability of flood and drought and flow diversion at Gazaldoba would only exacerbate the impact of the two hazards downstream.

- Interlinking of rivers by India: A narrative has also emerged in Bangladesh that the ruling Awami League has been “giving in” to India’s demands while getting nothing in return. This spans across various issues over shared rivers between the two countries such as the proposed Tipaimukh dam by India on a tributary of the Meghna river, the interlinking of rivers by India in the upstream, and the prolonged stalemate over the Teesta.

- Water diversion from Gazaldoba: More recently, the water diversion from Gazaldoba by India has also been linked to the growing food insecurity in the northwestern part of Bangladesh.

- As noted in a 2017 study, minimum flow in the Teesta dwindles to less than 200 cumecs (a cubic meter of water per second) during February which is insufficient either to operationalize Gazaldoba, which was designed by India to withdraw 520 cumecs or the Duane canal system in Bangladesh that is supposed to withdraw 283 cumecs in their full capacity.

- High water-consuming crops: In other words, there is not enough water during the lean season for either of the barrages to operate at full capacity. High water-consuming crops are another problem. The acreage of dry season paddy or boro—a highly water-consuming crop—has increased significantly in both North Bengal and northwest Bangladesh.

- Vote bank politics: Vote bank politics, however, have kept governments in both countries from attempting to counsel producers to diversify. An unregulated expansion in irrigation has created the acute shortage of water while the specificity of the basin and the unilateral water withdrawal by India to meet the irrigation requirements in North Bengal has brought the two countries at loggerheads.

So, is it a missed opportunity for India?

- It is tempting to conclude that India has missed an opportunity, but the devil certainly lies in the details.

- The Chinese investment is expected to enable Bangladesh to bolster its capacity and use more water from the river by improving water-use efficiency while reducing the losses from floods and riverbank erosion in the short-term (although it has also raised environmental concerns).

- However, the hydrological linkages between India and Bangladesh are a product of geography and a matter of shared history.

- Therefore, the opportunity to stitch an agreement over shared rivers, and particularly the Teesta, remains.

- The focus should further be on not just an agreement but an agreement that recognizes the needs of the ecosystem and explicitly recognizes and addresses the root of the problem—unsustainable use of water for boro

- India just needs to exercise its constitutional mandate to be able to do so, something that it has long been hesitant to do and pressure from improving ties between Dhaka and Beijing may be just the push it needs.

Conclusion:

This dispute has assumed importance in the recent years and is going to have serious ramifications in future unless both the nations took a serious look in the given dispute. It is high time that India is proactive in its engagement vis-à-vis shared rivers and act resolutely to usher a new era of hydro-diplomacy with Bangladesh. The Union Government in India just needs to exercise its constitutional mandate to be able to do so, something that it has long been hesitant to do, and pressure from improving ties between Dhaka and Beijing may be just the push it needs.

Solving the Teesta dispute, and cementing ties with Bangladesh, takes India further towards its goal of being a global leader. And to begin with-- the leader of its immediate neighborhood. More countries are disengaging with China. This is India's opportunity.