Introduction

The Eastern Corridor is a crucial highway for global trade flows, where any disruption could severely affect the global economy. However, the region, for years, have been characterised by tensions in South Asia and Southeast Asia.

It is important to study the interface between established maritime legal frameworks and spatial politics in the Eastern Corridor.

- The route comprises some of the world’s most vulnerable Sea Lanes of Communication (SCLOs), with potential flashpoints such as the South China Sea.

- Commercial exchanges are fundamental to global connections and have historically had a vital bearing upon the sustenance of nation-states and, specifically, on maritime politics.

- Shipping, one of the most globalised industries in the world, is the lifeblood of globalisation.

- The two share a symbiotic relationship: globalisation has increased the demand for maritime shipping, and maritime shipping has facilitated globalisation along with a transportation system that includes ocean and coastal routes, inland waterways, railways, roads and air freight.

- Indeed, the smooth functioning of commerce, coupled with a degree of control over resources and their acquisition, has been a key requirement of countries, especially growing economies.

- This in turn has influenced regional as well as global political relations.

- It is imperative to explore the gaps in the legal framework governing maritime security, and assess the potential risks of disruption not only in the economy but also in the rules-based global order.

What is the significance of sea lanes (Southeast Asia)?

- Global interactions take place along designated maritime highways known as Sea Lanes of Communication (SLOCs), facilitates an ever-expanding web of political and cultural associations.

- Since major actors are largely dependent on these SLOCs for commerce as well as their energy supply, the protection of the routes and competition over the resources they carry assumes strategic significance.

Sea lanes in Southeast Asia

In Southeast Asia, there are three key SLOCs:

The Strait of Malacca:

- It is the most important and most used sea lane

- It connects the Indian Ocean with the SCS

- It is the second-most important chokepoint in the world, after the Strait of Hormuz.

The Strait of Lombok:

- It is the safest sea lane in the region, it is wider and deeper than the Strait of Malacca.

- It is mostly preferred by large tankers and carriers transiting between the Persian Gulf and Japan.

The Strait of Sunda:

- Another substitute route for the Strait of Malacca, it has strong currents and limited depth, making it a less favored sea lane.

High Seas & Governance

- The high seas are crucial for global trade and commerce. They are home to SLOCs that act as maritime highways for the transport of cargo between countries and continents.

- The high seas are deemed as global commons: all countries are entitled to equal rights and access to peaceful exploration and resource exploitation.

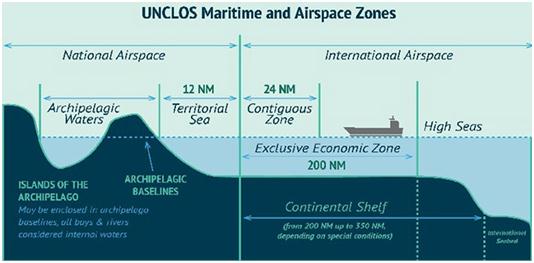

- In the purview of maritime law, the “high seas” encompass all parts of the sea outside of internal, territorial, contiguous waters and the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) of littoral countries.

- Increasingly, these commons are becoming more accessible with scientific and technological advances that expand the reach of physical connectivity, exploration, monitoring and, inevitably, surveillance.

- Already, parts of the deep seabed have ceased to be ‘free’, as the resources of these areas are explored and utilised.

- There is a governance structure for mining and undersea utilisation of the high seas under the auspices of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and the International Seabed Authority (ISA).

United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)

- The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) is an international treaty which was adopted and signed in 1982.

- It replaced the four Geneva Conventions of April, 1958, which respectively concerned the territorial sea and the contiguous zone, the continental shelf, the high seas, fishing and conservation of living resources on the high seas.

- The Convention has created three new institutions on the international scene :

- the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea

- the International Seabed Authority

- the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf

- International Maritime Organization: The UNCLOS has also established the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) as the standard-setting authority for the maritime and marine-related activities.

|

How world’s ocean spaces are demarcated?

The world’s ocean spaces are divided into five zones as given below:

- Territorial Sea:This area covers the immediate waters from the baseline up to 12 nautical miles.

- Coastal states have full sovereignty over this area, on matters of safety of navigation, protection of the marine environment, prevention and control of pollution, and the exploitation and use of resources.

- Such jurisdiction is the sole right of the coastal state, without any obligation to conform to international regulations.

- Contiguous Zone:Extending 24 nautical miles from the baseline is the contiguous zone, where the coastal state has authority with regard to customs, immigration, fiscal and sanitary laws.

- While the UNCLOS does not accord security jurisdiction to coastal states in this zone, increasingly, some states have asserted this authority, resulting in the practice being co-opted under customary international law.

- Exclusive Economic Zone:This zone stretches up to 200 nautical miles from the baseline.

- In this area, coastal states may exercise sovereign rights with respect to the scientific research, exploration, conservation, exploitation, and management of marine resources for economic activities.

- Other states hold the right to navigation, overflight and the laying of pipelines and submarine cables in any country’s EEZ, while coastal states reserve the right to any structural installations and constructions.

- Continental Shelf:The submerged prolongation of the landmass from the baseline constitute the continental shelf, comprising the slope, seabed and sub-soil shelf.

- It extends to the outer edge of the continental margin (till the beginning of the ocean floor) or up to 200 nautical miles, whichever lies farther.

- Coastal states have sovereign rights over exploration and exploitation of seabed and subsoil resources in this zone.

- High Seas:The maritime spaces that lie beyond the EEZ are defined as the high seas.

- All states have rights of navigation, overflight, fishing, scientific research, and the laying of pipelines and submarines cables in this zone.

- The flag state holds the right of jurisdiction over vessels in the high seas, except in the cases of piracy, drug and human trafficking, unauthorised broadcasting, and instances of statelessness.

Ocean Spaces and the Ambit of Legal Regimes

- Legal regimes in ocean spaces can be broadly classified into two main categories:

- The law of the sea: The law of the sea is part of public international law and governs the geographic jurisdictions of coastal states, and the rights and duties thereof for the use and conservation of the ocean ecosystem and its natural resources.

- It is distinct from maritime law, in that it relates to private laws of shipping and the commercial business of shipping.

- Maritime law: Maritime law, on the other hand, is often used synonymously with “admiralty law.” It applies to the private law of navigation and shipping in the inland waters of nations as well as in the high seas.

- International maritime law propounds the doctrine of freedom of the seas, which was first proposed by Hugo Grotius in the 17th century.

- The Declaration of Paris (1856), signed between 55 nations across Europe and the Americas, obligated its signatories to respect the prevalent principles of maritime law during wartime as well.

- However, their acceptance and practice only commenced much later, with the rise of maritime commercial nations such as Great Britain.

- Freedom of the seas gradually came to include the freedom of navigation, overflight of aircraft, the laying of submarine cables and pipelines, fishing and, by the 20th century, exclusive offshore-fishing rights and the conservation and exploitation of maritime resources, especially oil.

- The laws of the sea are designed to preserve order in the high seas, with respect to territorial waters, sea lanes, and ocean resources.

- The UNCLOS (1982) is the primary and most comprehensive foundation for these laws. Over the years, there have been many attempts to codify the law of the high seas, leading to the establishment of several global institutions that govern different aspects related to the laws in their current form.

- Nevertheless, several issues remain unresolved.

Why maritime security is important?

- The modern global economy has been made possible largely due to the maritime movement of goods, enabled by maritime security.

- Over the past 50 years, shipping costs having consistently fallen, further encouraging the dispersion of manufacturing and retail.

- Efficient, timely maritime transportation has become central to economic competition, for both individual businesses and national economies.

- Since the SLOCs are vital to the smooth functioning of economies, potential sources of disruptions must be examined and addressed on priority.

- Maritime trade operates in the global commons, and the safeguarding of maritime transport networks must happen at a global level through a multi-stakeholder model.

SLOC Security in the Eastern Corridor

- Historically, human interactions that take place in the oceans have given rise to cross-cultural and commercial linkages, which are the foundation of prosperous civilisations. Thus, maritime routes have always been based on the principle of free passage.

- With time, and with the advancement of exchanges and modernity, these sea routes came to be organised, monitored and legally classified.

- Today, SLOCs form a complex network spanning the globe and ensure the seamless functioning of a logistics system that is fundamental to the global economy.

- The East–West Corridor, or the Eastern Corridor, is a long and busy network comprising several maritime routes that link major industrial centres of North America, WesternEurope and Asia.

- The nations along this corridor are dependent on the security of SLOCs.

- However, the preservation of navigational safety and security cannot be carried out and sustained by individual countries, companies, or stakeholders.

- There are many dimensions to the security of SLOCs, such as physical attacks to vessels, disruptions to navigational access, risks of accident, and environmental concerns.

- The sheer scope demands concerted efforts for a thorough understanding and assessment of the risks involved, the identification of potential flashpoints, and the consideration of political sensitivities.

- With globalisation increasing interdependencies and aspirations, leading to a rise in trade and connectivity, the security of SLOCs is becoming increasingly important.

Which is the most vulnerable SLOC?

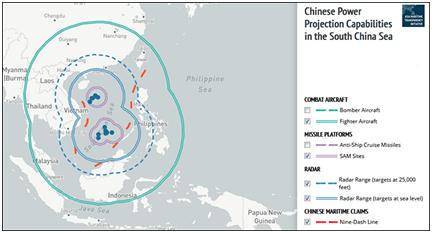

- The composite geography and the decades-long intense geostrategic tensions make the SCS one of the most vulnerable SLOCs in the entire world.

- Moreover, the geography of this sea space lends itself considerably to jurisdictional ambiguity, which further exacerbates geopolitical tensions.

- Littoral states, including China, hold varying interpretations of the law of the sea, stymieing the efforts towards mitigating the disputes that characterize it.

- These challenges have cleared the way for what is referred to as “grey-zone situations,” officially acknowledged in Japan.

- Grey-zone situations indicate “confrontations over territory sovereignty and economic interests that are not to escalate into wars.”.

South China Sea

- The South China Sea – a crucial passage for a significant portion of the world’s commercial shipping – is bordered by Brunei, Cambodia, China, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Taiwan, Thailand, and Vietnam.

- China claims roughly 90% of the sea, which encompasses an area of around 3.5 million square kilometers (1.4 million square miles).

|

What factors lead to maritime threats?

- Threats to freedom of navigation and SLOC security could arise out of

- attempts by coastal states to control the rights of passage due to national security concerns

- domestic instability

- tensions over competing and overlapping maritime territorial claims

Classification to threats

With regard to SLOC security, threats can be classified into two broad categories:

- Wartime threats: The former includes blocking the movement of naval and merchant ships, and maritime interdiction operations.

- While the possibility of war cannot be ruled out entirely, the instances of such events have declined since World War II, making these threats less acute than they used to be.

- Peacetime threats: Peacetime incidents, therefore, are the main source of threat at sea in current times, perpetuated mostly by non-state actors and complicated by the proliferation of open registries.

- Traditional and non-traditional threats: Threats to SLOCs can be further categorised into traditional and non-traditional threats, the former comprising incidents such as piracy, trafficking and smuggling, and the latter comprising militarisation, territorial conflicts and so on.

Concerns regarding maritime laws

- Increase of illegal activities: Much of geopolitics in the last few years has revolved around maritime geostrategy, including cases of unlawful claims, aggression, and challenges posed to the freedom of navigation and stable seas.

- Avoided geostrategic threat: Maritime law covers the spectrum of a state’s actions with respect to its designated maritime territory as well as commercial shipping regulations. However, maritime law remains ambiguous in relation to the geostrategic threats perceived by states with respect to the high seas.

- Unaddressed state actions: Additionally, these laws primarily concern themselves with peacetime threats at one end of the spectrum of conflict, and situations of war at the other, without addressing the possibilities of state actions in between.

- States, therefore, in response to maritime strategic threats are often forced to either develop their own naval capabilities or forge security alliances.

Right to freedom of navigation

- The main objective of the UNCLOS is to standardise protocols and encourage nations to draft their regulations in accordance with global best practices.

- This is aimed at balancing overlapping rights and obligations, and ensuring equitable access of the seas to all states, whether coastal or landlocked.

- The UNCLOS aims to facilitate international communication; promote the peaceful uses of the seas and oceans, and the equitable and efficient utilisation of their resources; the conservation of their living resources; and the study, protection and preservation of the marine environment.

- In this regard, the UNCLOS has defined the limits of sovereign waters for every state and their rights over the resources of such zones.

- There are three components of the rights to freedom of navigation:

- innocent passage through territorial waters

- transit passage through international straits as well as territorial waters for continuous and expeditious journey

- archipelagic sea-lanes passage

- According to Article 19 of UNCLOS, the first should not be prejudicial to the peace and stability of the coastal state.

- The article lists 12 activities that fall into the category of being “prejudicial.”

The shift from Asia-Pacific to Indo-Pacific

- In 2017, Japan declared an "Open and Free Indo-Pacific" as part of its regional strategy.

- India followed with an "Act East" policy that gave added purpose to its earlier "Look East" doctrine.

- The US outlined its "Free and Open Indo-Pacific" vision in its National Security Strategy in 2017.

All three major powers have signalled that the concept of Asia-Pacific is becoming outdated, and that Indo-Pacific better fits the international order in the 21st century with its growing strategic competitions.

Major challenges for the region

- High vulnerability: The composite geography and the decades-long intense geostrategic tensions make the SCS one of the most vulnerable SLOCs in the entire world.

- Increasing stakeholders: The ever-increasing number of stakeholders further adds to the risks of competition.

- Governance issues: While this is a testimony to progress and a more extensive understanding of deep-ocean ecosystems, it brings up a host of issues in governance, the scope of permissible activities, and safety measures in case of untoward incidents.

- Overexploitation: Concerns related to the exploitation of the deep seabed stem from its potential adverse impact on the fragile marine ecosystems.

- Disruptions: Maritime trade encompasses various security considerations intertwined with the interests of businesses, governments and consumers. This interconnectedness makes the transportation network vulnerable to disruptions, which affects supply chains that support global commerce and national economies.

- Geopolitical tensions: Moreover, the geography of this sea space lends itself considerably to jurisdictional ambiguity, which further exacerbates geopolitical tensions. Littoral states, including China, hold varying interpretations of the law of the sea,stymieing the efforts towards mitigating the disputes that characterise it.

Conclusion

The importance of ocean is growing for states with rising dependence of states on sea-borne trade. With increasing globalization and maritime domain awareness, countries have started to streamline their maritime policies and are becoming concern about their marine resources given the strong belief that world economy is becoming ocean-based with rich trade and resource potential and termed as blue economy.