‘The Battle over Forestland’

- Posted By

10Pointer

- Categories

Polity & Governance

- Published

20th Jan, 2021

-

-

Context

The forest land right claims by tribal or pastoral communities seeking community rights over forest land, they have inhabited for generations, end in rejection (mostly) in the country.

The failure of the system raises concerns and calls for transparent recognition of forest dwellers’ rights.

-

Background

- In India, tribal and other traditional forest dwelling communities had historically faced injustice at the hands of a colonial forest bureaucracy.

- Alienation of land, restriction of access, forced evictions and lack of decision making over managing these lands are only a few manifestations.

- Fabricated arrests on account of trespass, ‘connivance’ with poachers and timber mafia have been other areas of conflict.

- Even today, the situation has not changed much. Both tribal and other traditional forest dwelling communities living in the forests for years have to fight for their own land and it goes on for indefinite years.

- While forest bureaucracy has been trying to undermine reforms in forest governance in India, the need for community level forest governance is more urgent than ever.

|

The case of unsettled rights

- On a January night in 1967, Vanthala Ramanna became an encroacher on his own land.

- The Andhra Pradesh government snatched away his land when it decided to create a new reserve forest almost the size of Mumbai city.

- The news reached Panasalpadu village in Vishakhapatnam district almost two days later. By then, Ramanna and all others in the village had become de facto landless who had to prove their land ownership.

- The notification was issued under Section 4 of the Indian Forest Act, 1927.

- It is the first step in the process of declaring any piece of land as a reserve forest.

- The next steps involve settling the land rights before the transfer is made to the new owners — the forest department. But that never happened.

- This is not the first time the village residents had to prove their rights over their ancestral land.

- Cut to January 2021. Ramanna is dead, but the fear of being evicted from their own lands haunts his family.

- It has been 50 years and the government has neither established the reserve forest nor returned our land,” says Vanthala Chinnaya, Ramanna's son who was not even born when the notification was introduced.

- He is now a grandfather of two.

- Andhra Pradesh is not the only state where this legacy of unsettled rights over forestland haunts communities. Large swathes of forestland and their millions of inhabitants across India are in a similar limbo.

|

-

Analysis

How a forest is formed?

While the process is well defined under the Indian Forest Act, 1927, there is no time limit, which is the loophole behind the indefinite delays.

|

Step 1- Expressing the intent:

|

- Under Section 4 of the Indian Forest Act, 1927, the state government first issues a notification in the official gazette which broadly specifies the limits of the proposed reserve or other intelligible boundaries.

- It then appoints a forest settlement officer (FSO), who should not hold a forest office.

- Under Section 5, all rights of cultivation or other activities are suspended in the area, unless granted by the state government

|

|

Step 2- Call for Claims:

|

- Under Section 6, FSO informs the people, through the vernacular press, about the Section 4 notification and how it impacts their rights.

- · The FSO then fixes a period of not less than three months for the people to submit their claims.

- If the claims are not submitted to FSO within the stipulated time, under Section 9, they stand extinguished.

- The FSO can received claims for individual and common land, including areas used for shifting cultivation

|

|

Step 3: Inquiry:

|

- Under Section 7, the FSO inquires into the claims received for individual rights and any other rights that he/she may find in the government records.

- Once the inquiry is completed, the FSO, under Section 11, passes and order admitting or rejecting any individual rights.

- Under Section 12, the FSO adjudicates common lands used for pasture or forest produce collection and either admits or rejects the claim.

- Under Section 10, FSO records if there is shifting cultivation and any local rule or order permitting it.

- Only in the case of shifting cultivation, the FSO gives his opinion to the state government, which can take a call on whether to allow it, modify it or prohibit it.

|

|

Step 4- Acquiring land:

|

- In case, the FSO admits these rights, the land in question is either excluded from the proposed reserve forest, the right holders could surrender the rights, or the land is acquired.

- Under Sections 15 and 16, if the rights are settled then an order is passed to that effect, otherwise payment for land acquisition is made.

|

|

Step 5- Appeal:

|

- The claimants or the forest department can appeal against the FSO order to a revenue official not below the rank of a collector or to a forest court, if it has been established by the state government.

- The individual can do the same within three months of the order under Section 17.

|

|

Step 6- Announcing a reserve forest:

|

- After all the rights are settled, appeals are disposed of and the land acquired, the state government publishes the exact boundary of the reserve forest and the date from which it was reserved in the official gazette under Section 20.

|

-

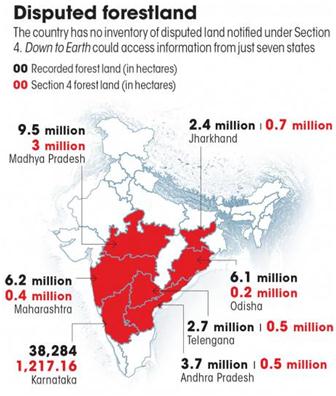

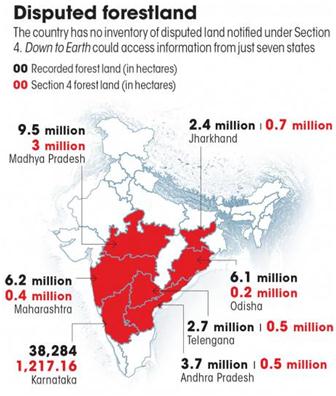

Disputed Forestland

- The Indian Forest Act, 1927, recognizes only three categories of forests:

- Reserve

- Protected

- Village

- Still, the land records of almost all forest departments have “Section 4 forest” as a category, as if it is an unsaid rule.

- There is, however, no consolidated data on the extent of this ad hoc forestland.

- Such government inaction means that even those forests whose protection triggered the entire process, are now left vulnerable.

- Under the Indian Forest Act, 1927, once the notification under Section 4 is issued, the state government has to appoint a forest settlement officer (FSO) to look into the land rights of people living within the identified boundaries of the proposed reserve forest.

- The officer has the power to settle rights over both common and private lands.

- The claimants can also appeal against the decision of FSO in a forest court.

- Only when this process of land settlement is complete, including the verdicts on the appeals, can the state government issue a notification under Section 20 of the Act to finally declare a piece of land as a reserve forest.

- Currently, 14 states have their own forest laws, but all follow a similar procedure.

- While the law says the FSO has to fix a period within which people can submit their claims, it has no time limit for the rest of the process.

|

Concerns over Section 4 lands

- Forest departments across the country treat the areas stuck under Section 4 as their own land, even without completing the process.

- The Indian State of Forest Report, 2019, released by the Forest Survey of India, offers a glimpse of this.

- It says while the total recorded forestland in the country stands at 76.74 million ha, only 51.38 million ha of it has forest cover.

- This means 25.37 million ha forestland is without a cover.

- This includes Section 4 lands, along with forestland diverted for activities like mining, hydropower projects which lack any forest cover now.

|

-

-

Forest encroachment

- Nearly 2%, or 13,000 sq km, of India’s total forest area is occupied by encroachers, as per the environment ministry.

- Madhya Pradesh tops the list with 5,34,717.28 hectares of forest land under encroachment, followed by Assam at 3,17,215.39 hectares and Odisha with 78,505.08 hectares.

- Uttarakhand is not too far behind, with 10,649.11 hectares of forest land under encroachment.

- India’s total forest cover is 708,273 sq km.

- Only 3% of community forest resource rights [right of forest dwellers to protect, regenerate, conserve or manage any forest resource] have been approved under the Forest Rights Act.

- Only 10 to 13% of individual forest rights have been recognised so far.

|

-

What is the root cause of debates and conflicts?

- Forest issues in India are multilayered and complex and conventional perspectives from the point of view of environmental economics and common property resource theory are inadequate to address the challenges arising in managing forests in India.

- The roots of the current controversies can be traced to forest governance practised during the British rule, which continues to impact/influence how forests are governed in the present times.

- During the colonial rule, the British government took over India’s forests and managed them under the Indian Forest Act (IFA) of 1878, which was revised in 1927.

- The Act created two main categories of forests, managed by the Imperial Forest Department(FD):

- Reserved Forests (RF)

- Protected Forests (PF)

- The main focus of the forest department in colonial times was to generate revenue through timber and softwood production.

- Forest dwellers were deprived of their livelihoods in the process as shifting cultivation and grazing were banned.

|

- The same understanding of forests continued after independence when the area under RFs and PFs was expanded and their ownership was nationalised among princely states and zamindari or other forms of ownership.

- The newly formed states also continued with the same IFA, and the imperial FD became state FDs, run by the Indian forest service.

- The Wildlife Protection Act was passed, and wildlife conservation replaced timber production, but the conservation policy continued to exclude local communities.

- Many local communities thus became encroachers on their own land and were forced to resort to theft, leading to punishments, exploitation and further alienation from the forests that they belonged to.

- While the situation changed to some extent after independence when local communities gained concessions to enter forests, access rights helped very little without management rights, thus leading to degradation of forests.

- Then came the the Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act 2006, also known as FRA.

|

India’s recognition of tribal rights

- India is a signatory to:

- the UN Declaration on Rights of Indigenous Peoples

- the Universal Declaration on Human Rights

- India has ratified the Indigenous and Tribal Populations Convention

- The country is party to the Convention on Biological Diversity

|

-

Where did the FRA fail?

- The FRA has helped greatly in taking power away from state bureaucracies into the hands of the communities.

- It focuses on community forest management based on sustainability and conservation and ensures that communities will not be displaced from protected areas unless demonstrated through due process.

- The implementation of the FRA, however, has been mired with conflict and bureaucratic resistance leading to the controversial interim court orders of February 2019.

|

The SC Order (2019)

- On February 13, 2019 the Supreme Court ordered the eviction of more than 10 lakh Adivasis and other forest dwellers from forestland across 17 States.

- While the SC has later made it clear that there will be no forcible eviction, what the order has succeeded in doing is resuscitating a sharp binary between the human rights- and wildlife rights-based groups that have for decades tried to swing public opinion in their favour.

|

-

Roadblocks

- Low priority for state machinery

- Lack of transparency

- Lack of awareness and misinformation

- Ineffective documentation

- Intra-society dynamics

-

Way forward

There is urgent need for community level forest governance in the forest bureaucracy. The complex multi-stakeholder and multi-scale nature of the forest resource implies that community-level forest governance needs some form of regulation. But this regulation needs to be accompanied by checks and balances to safeguard against its abuse taking into consideration the colonial roots of India’s forest bureaucracy. Thus newer and more democratically accountable structures need to be thought of.