Introduction

- On 11 March 2020, WHO declared Novel Corona virus Disease (COVID-19) outbreak as a pandemic and reiterated the call for countries to take immediate actions and scale up response to treat, detect and reduce transmission to save people’s lives.

- Novel corona virus SARS-CoV-2 marked the third introduction of highly pathogenic and large-scale epidemic corona virus into humans after SARS and MERS.

- Several research groups’ studies suggested that it is likely the zoonotic origin of COVID-19 and person to person transmission has led the pandemic disease.

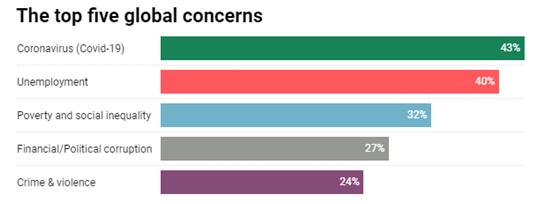

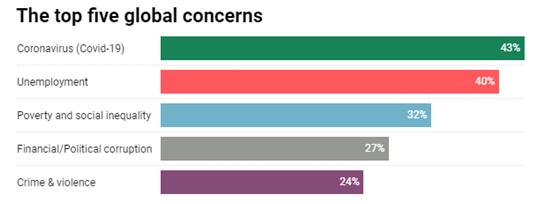

- After Corona virus, Unemployment is the second highest ranked global concern at 40% and is the top worry in eight countries.

- The countries currently most worried about Unemployment are Italy (62%), South Africa (60%), South Korea (59%) and Spain (also 59%).

- There are no major changes in the rankings for Poverty & social inequality or Financial/political corruption, however Crime & violence replaces Healthcare as the fifth top global worry this month.

COVID-19 as a global challenge: towards an inclusive and sustainable future

- COVID-19 is a global challenge that demands researchers, policy makers, and governments address multiple dimensions which go far beyond the implications of this pandemic for health and wellbeing.

- Just as the UN Sustainable Development Goals call for focus on the connections between development policy sectors, the pandemic has exposed the complex global interdependencies that underpin economies and highlighted fault lines in societal structures that perpetuate ethnic, economic, social, and gender inequalities.

- In 2018, 820 million people worldwide were experiencing chronic hunger; by 2019, those living with acute, crisis-level food insecurity had increased from 113 million to 135 million.

- COVID-19 could almost double this number to 265 million by the end of 2020.

- The poorest of the poor are the most vulnerable to the compounding impact of COVID-19 on the global food system, including its effects on food production (planting and harvest), transport, processing, and safe distribution to and from local markets.

- Without international collaboration, protectionist measures by national governments and disrupted supply chains could cause food shortages, increasing food prices worldwide.

- Natural disasters: On top of the pandemic, agricultural and natural disasters such as extreme weather events (requiring years of recovery), plagues of locusts, and armyworms sweeping across continents are hurting food production and creating further stress on local, national, and regional food systems across the world.

- Education crisis: COVID-19 is also creating an education crisis. Most governments around the world have temporarily shut schools in an effort to enforce social distancing and slow viral transmission.

- The UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) estimates that 60% of the world’s student population has been affected, with 1·19 billion learners out of school across 150 countries.

- Loss of access to education not only diminishes learning in the short term but also increases long-term dropout rates and reduces future socioeconomic opportunities.

- The consequences of COVID-19 school closures are predicted to have a disproportionately negative impact on the most vulnerable and risk exacerbating existing global inequalities.

- Vulnerable children will have fewer opportunities to learn at home, face greater risk of exploitation, and may lack adequate food in the absence of access to free or subsidised school meals.

- The responses of education systems to COVID-19 need to be particularly cognisant of cultural and contextual factors, including gendered, socioeconomic, and geographical differences, in order to ensure that they do not exacerbate inequalities.

- Conflict: Even without a pandemic, conflict is often the ultimate social determinant of health, producing a wide variety of health challenges ranging from constraints on health systems to difficulties in delivering and accessing health services.

- COVID-19 amplifies governments’ potential to exercise unlimited executive powers that might exacerbate conflicts and have a devastating impact on conflict-affected populations.

- The UN Security Council’s call for a global ceasefire to allow access to vulnerable populations for prevention of and response to COVID-19 has not been heeded, and there is increasing exchange of artillery and shelling across some of the oldest conflict fault lines.

- International agreements, treaties, and peace agreements have been disregarded as the world focuses on COVID-19.

- Furthermore, as noted by the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, there has been an alarming rise in police brutality and civil rights violations under the guise of exceptional or emergency measures.

- Mobility: One of the first manifestations of efforts to control the spread of COVID-19 has been to try to restrict people’s movements; yet staying at home is a luxury only some can afford.

- Restrictions on mobility could have devastating effects on the world’s 79·5 million displaced persons, many of whom live in crowded conditions with limited access to employment or services.

- COVID-19 might be the first major challenge to the Global Compact on Refugees and the Global Compact on Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration, both of which promise a “whole of society approach”.

- Displacement: The pandemic brings a real danger that displaced populations will be excluded from access to health care, economic safety nets, and recovery efforts, and that their very status as migratory or displaced persons will lead to their being scapegoat as a threat to settled populations, reinforcing their isolation and exclusion.

- Transmission in urban areas: The common pathogen exchange pathways and mechanisms of COVID-19 transmission are intensified in dense urban environments, so it is no surprise that 95% of all COVID-19 cases globally have occurred in urban areas.

- Epidemic control is therefore also a key consideration in urban planning.

- Nearly one billion people live and work in informal, under-serviced, and precarious urban conditions worldwide, while billions more rely on patchy and unreliable piped water, electricity, and health-care access in cities with deteriorating infrastructures.

- Essential work: Limitations of the precarious spaces in which people live and work mean it is virtually impossible to isolate those with symptoms, while reliance on informal providers of medicines and health-care services means there is limited evidence of disease burdens.

- High-risk essential work, such as cleaning and waste processing, constitutes some of the lowest paid work.

- Furthermore, urban lockdowns have led to substantial job losses and economic hardship for both domestic and international migrant workers and their families.

- Fall in remittances: Globally, there have been sharp falls in the remittances that support millions in low-income countries; in sub-Saharan Africa, inward remittances in 2018 amounted to US$46 billion, dwarfing foreign direct investment at $32 billion for that year.

- Up to 16% of GDP across Africa is from remittances, much of which comes from European countries currently in lockdown.

- Unemployment: Rapid imposition of movement restrictions has also left migrant labourers tranded while facing sudden unemployment.

- Short-term climatic relief: COVID-19 brings a short-term climate dividend with benefits including cleaner urban air, but a post pandemic economic recession could divert attention from the underlying climate crisis.

- Renewal packages might miss opportunities for restructuring towards greener technologies; many countries are planning big investments in fossil fuel industries.

- In Europe and the USA, governments have agreed financial aid to the aviation sector with no binding environmental conditions.

- Equally, countries already at risk from humanitarian crises and natural disasters could face a threefold greater risk of exposure to COVID-19, while having six times less access to health care, than the countries at lowest risk.

- Compound disaster events: Simultaneously, the pandemic elevates the likelihood of compound disaster events, especially for the nearly one billion people exposed to flooding.

- June is the start of the hurricane season in the Caribbean and the monsoon in south Asia; summer heat in North America and Europe will also disproportionately affect the elderly and those with underlying health conditions.

- Agile and urgent responses to specific needs rising from the complex emergency of the current pandemic are clearly crucial. Mitigation measures that are affordable and appropriate for diverse resource poor environments are urgently required.

- Yet as the multiple impacts of both the pandemic and public health responses to it continue to unfold, the complex interlink ages between these impacts challenge the global community to move beyond sector-specific crisis reactions.

Re-conceiving the scenarios presented above in terms of risks, consequences, and opportunities provides new ways to consider responses that cut across specific domains. Thus pandemic-induced lockdowns leading to economic crises, or reorientation of health services to COVID-19 care producing subsequent rises in morbidity and mortality from other conditions, can be understood as cascading risks associated with dynamic vulnerability, whereas disruption to food supply chains compounded by the coming monsoon, or refugee camps having heightened vulnerability to COVID-19 mortality, exemplify overlapping risks.

Other impacts on Health

Health, social, and humanitarian sectors will be stretched to cope with overlapping events, especially under the global economic recession.

- Domestic violence and mental health issues: Beyond COVID-19 itself, public health measures to contain the pandemic have produced alarming increases in domestic violence and mental health problems.

- Childhood malnutrition: Further adverse effects are likely to include rising childhood malnutrition and potentially rickets and, in the longer term, increased incidence of chronic conditions due to reductions in physical activity and income.

- Increased suicide rates: The global economic recession will produce increases in suicide rates among those hit hardest.

- Antimicrobial resistance: Antimicrobial resistance could increase following extensive antibiotic use for patients with COVID-19 and interrupted treatment of existing conditions.

- Underfunded system: Reorientation of health facilities to deal with COVID-19 in already overstretched and underfunded health systems has reduced capacity to manage existing disease burdens; cessation of routine surgeries, health checks, and immunisation programmes might produce outbreaks of preventable communicable diseases, rising cancer rates, and increasing numbers of late-stage complex medical conditions.

However, previous experiences with tuberculosis, HIV, Ebola virus, and severe acute respiratory syndrome corona virus (SARS) are producing more rapid and effective responses to COVID-19 in some countries than elsewhere. Temporary gains include fewer road accident injuries and respiratory problems from air pollution, and reductions in diarrhoeal and other communicable diseases during social distancing.

India’s medical diplomacy during COVID-19

In the wake of this pandemic, India has advocated availability of medicines across the globe through international cooperation and development partnerships.

- UN Resolution: Notably, India signed a UN resolution to ensure fair and equitable access to essential medical supplies and vaccines developed to fight COVID-19.

- India’s recent efforts to export Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) to affected countries around the world are based on India’s history of medical diplomacy.

- Additionally, consignments of HCQ and paracetamol are being exported to 87 countries. This can be classified under trade modality of SSC. Multilateral agencies such as UNICEF too have been provided with global supplies by India.

- South Asia

- Adhering to the ‘neighbourhood first’ policy, India has sent the HCQ tablets to Afghanistan, Bhutan, Bangladesh Nepal, Maldives, Mauritius, Sri Lanka and Myanmar.

- Furthermore, Indian military doctors have been deployed in Nepal and Maldives to support that local management in their response to COVID-19.

- PM also pledged USD 10 million as India’s contribution for the fund, thus assuming the leadership of the region’s charge against the pandemic.

- West Asia

- India is simultaneously strengthening ties with the Middle East by supplying HCQ tablets to Saudi Arabia, UAE, Oman, Syria and Jordan among others.

- UAE and Saudi Arabia are two of India’s key trading partners.

- Additionally, the recently signed MoUs focuses on strengthening bilateral engagements in the health and medicine sectors.

- India has also discussed COVID-19 mitigation measures with Jordan while the country has deployed medical professionals in Kuwait.

- Africa

- As a part of an ‘Africa-focus working day’, the Indian External Affairs Minister held a series of conversations with his counterparts of Nigeria, Niger, Burkina Faso, Uganda and Mali, and promised support and medical assistance.

- Subsequently medical assistance was provided to another twenty African countries.

- India, which has been a major exporter of medicines to Africa even before the corona virus pandemic, has been exporting drugs and medical devices on a humanitarian basis, living up to its status of being “pharmacy to the world”.

- Further, the Indian PM took personal initiative to call beside others, Heads of State of Egypt, Uganda and South Africa, to assure support in combating the pandemic. This is especially relevant given the India-Africa Summit.

- Latin America and Caribbean

- As a part of India’s efforts to support Caribbean and Latin American countries, India had pledged five million HCQ tablets for 28 countries as grants.

- Brazil, Argentina and Colombia, have temporarily scrapped import duties on specific respiratory equipment from India whereas Colombia, Paraguay and Ecuador, have done so on medical equipment such as gas masks and oxygen therapy devices.

- India will be donating 4000 HCQ tablets as grants and providing 19,200 tablets on commercial basis to Jamaica.

- This comes after India had committed US$ 1 million grant funding for community development projects in Jamaica in the India- CARICOM 2019 summit.

- Apart from providing medical supplies through grants and commercial means, India has also been facilitating the transfer of skill and knowledge to medical professionals through the capacity building modality of South South Cooperation.

- Indian medical staff has been conducting online training for their counterparts from other SAARC, Caribbean and Latin American countries.

- According to UN Office of South South Cooperation, India, Brazil and South Africa’s Facility for Poverty and Hunger Alleviation (IBSA Fund) that works towards supporting key e-Learning project to improve health-care coverage and quality in the northern Vietnam has proven to be successful in reaching health-care workers in remote medical settings as a part of their response to COVID-19.

- In addition to extending support to the global South, India has also reached medical supplies to developed Northern countries such as USA, Spain, Bahrain, Germany and the United Kingdom under commercial agreements signed with Indian pharmaceutical companies.

- This is notable, given the infamously stringent pharmaceutical standards set by these countries.

- Given limited resources and huge domestic demand, India’s leadership in the global contest during the pandemic has earned India well-deserved goodwill.

- These efforts can be contrasted with the Chinese providing medical supplies and equipment including test kits, which have been less than effective on many occasions.

- Given the predicament, India’s medical diplomacy is enabling India to emerge as a responsible and reliable player during a time when many established international actors have failed to do so.

India’s capability in tackling COVID-19

- Atmanirbhar Bharat: Outside health policy, India’s weak economic response is a big problem. The Atmanirbhar Bharat (“Self-reliant India”) stimulus package announced in May is not small at $110 billion; this is equivalent to 10 percent of India’s GDP. But it comprises mostly monetary interventions to provide liquidity with a longer-term outlook to boost the economy.

- Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Yojana: In terms of funding responses and relief measures targeted at the poor and vulnerable, the $23 billion Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Yojana relief package falls short as it mostly reallocates funding across existing budgets or allows people to make advance withdrawals on their social benefits rather than mobilizing additional funding.

- India needs to do more to help the families of low wage workers displaced from their jobs by the lockdown and the weakening economy.

- Poor health infrastructure: For the health sector the main problems is low levels of testing, implementation failures in containing the spread during lockdown, and serious impacts on other health services.

- In the longer term, what is required are investments in health infrastructure, ensuring continuity of regular health services, and improving health emergency preparedness.

- Rising unemployment: India will have to cautiously adjust spending, attract industrial investments to spur growth, and address rising unemployment. But over the next year, India can expect to remain in crisis mode.

What needs to be done?

- Based on the current status of COVID-19 and the lessons from its early response, India ought to be prioritizing five measures:

- Increase testing capacity: India can do this quickly by harnessing the capacity of the private sector for laboratories, test kits, and supplies. But the government will also have to increase the density and capacity of test sites and laboratories and improve procurement and supply chains. India’s domestic PPE kit production has been a great success story, which provides reasons for optimism.

- Assist poor workers: Steps to help poor migrant workers include programs offered by the Ministry of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation in their 2017 report. These policies include provision of affordable housing, emergency employment schemes, and access to social entitlements and service provisions. The recent announcement on provision of essential food supplies to 800 million people is a step in the right direction.

- Maintain regular health services: Maintain essential critical health services and disease programs to avoid a resurgence of vaccine preventable diseases, infectious diseases, and chronic illnesses. Both the central and state governments should look to expand strategic investments and partnerships with the private sector, development partners, and community health workers to strengthen surge capacity and ensure continuity of health provision.

- Enforce emergency measures: Enforce sensible social distancing, effective quarantine procedures, mandatory mask-wearing and hand hygiene habits, along with improved detection, containment, and mitigation.

- Enable responsible monitoring: Introduce and ensure national data privacy laws to improve India’s health emergency response and safeguard against data privacy concerns.

What kind of tests is India using?

- Feluda: The latest one gives fast results, like a pregnancy test, and is named after a fictional Indian detective character, called Feluda.

- Crispr: It uses a technique known as Crispr - short for Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats - which is a gene editing technology.

- Gene editing works in a way similar to word processing, and can scan DNA to make microscopic changes to the genetic code. It's been used to treat ailments like sickle cell disease.

- PCR: The one that's been most commonly used globally is a PCR (polymerase chain reaction) test, which isolates genetic material from a swab sample. Chemicals are used to remove proteins and fats from the genetic material, and the sample is put through machine analysis.

Conclusion

This reframing enables identification of potential responses to best address different intersecting risk scenarios and to consider their consequences for resilience, such as what COVID-19 means for future urban planning or food supply chains. Finally, it invites us to identify transformative opportunities, such as the impetus provided by temporary shifts in working practices and transport patterns for longer-term changes to mitigate future crises of planetary health and personal wellbeing. The pandemic has offered us a collective glimpse of alternative possible futures and opportunities. Tackling the persistent root causes of risk that are reproduced through inequitable development processes and persistent poverty will allow the Sustainable Development Goal of equitable and sustainable development to be realised for all.